On July 11, 1656, two Quaker women, Anna Austin and Mary Fisher, came to Boston to preach, as they themselves confessed, their new doctrine. They were immediately imprisoned and their books were burned. Only after they had languished in prison for five weeks were they taken across the border.

|

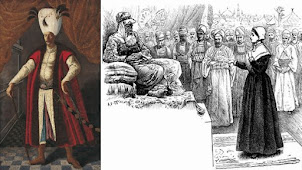

| Sultan Mehmed IV; Mary Fisher before him |

Mary Fisher then traveled to Adrianople and had an interview with the Grand Duke of the Turks [Sultan Mehmed IV]. Eight other Quakers who arrived [in Massachusetts] soon after were treated in the same way. *) The commissioners, at present assembled at Boston, recommended to all the New England colonies to prevent, by laws, the immigration of Quakers and other public heretics, and, if they should yet be recruited, to arrest and remove them. Laws to this effect were passed; only not in Rhode Island, which in its written answer rather stated that the Quakers would soon calm down, if one would only stop persecuting them; — that they had at first caused disturbances there, too, but now blasphemed Rhode Island as a country that gave them no opportunity to prove their "patient suffering". († Grahame's Hist. p. 240)

______________

*) Among them was a certain Marie Clarke, the wife of a tailor in London, who had left her husband and six children to carry to New England a message "which," as she asserted in her rapture, "she had received from heaven." (Grahame's Hist. p. 240.)

In Massachusetts it was forbidden, under severe penalty, to bring a Quaker into the country or to harbor him. If one of this "accursed sect" was found within the colony, he was to have one ear cut off; if he returned again, he was to lose the other; and if he was found a third time, his tongue was to be pierced with a red-hot iron. It really happened to three Quaker preachers that each of them had an ear cut off.

But it was just such laws that attracted the Quakers to Massachusetts; they wanted thereby to show their zeal, their courage of faith, and probably also to obtain the crown of martyrdom. They did not respect fines, public flogging and other torments. At last, the authorities went so far as to threaten with death those who would allow themselves to be caught for the second time <p. 32> within the borders of the colony. *) This did not help either!

_____________

*) This law, at first rejected by the representatives, at last passed by a majority of one vote at the close of 1659. (Grahame's Hist. p. 241.)

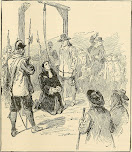

William Robinson and Marmaduke Stephenson were the first to be hanged because they were Quakers and would not shun the land. Mary Dyer stood under the gallows and rejoiced to be allowed to die for the sake of her faith. She was "pardoned" for this time, however, and taken across the border. Soon, however, "the spirit drove her back" and now she too was hanged. Before she died, she testified with great earnestness that she was suffering for the sake of her conscience. Not long after this William Leddra was also killed; but now the people began to murmur at such cruelties.

Wenlock Christison was also to die. But he told his judges that they had no right to kill him, and that by doing so they had transgressed the laws of England, for which reason they would have to expect temporal and eternal punishment. "And," said he at last, "it is all in vain, for everyone you kill there come five others. In my stead shall be ten, that ye shall have plague upon plague; that is your portion, for the wicked have no peace." Be it that the conscience of the authorities awoke, or that fear took possession of them, they let Christison out of prison with twenty-seven others, and contented themselves with having a man and a woman whipped through the streets. This remained the punishment of discovered Quakers for the next period, until finally King Charles II interceded for them and forbade further persecutions.

Christians of all denominations were tolerated in Rhode Island; only "Papists" were not allowed to be seen there. Cotton Mather therefore said (1655): "The colony of Rhode Island is a mixture of Antinomians, Fatalists, Anabaptists, Arminians, Socinians, Quakers, and everything but Romanists and true Christians; bona terra, mala gens (i.e. good land, bad people)." — They only tolerated preachers who wanted to work "for nothing"; they did not think much of "clergymen" at all; but young and old are said to have read the Bible diligently.

In order to sufficiently characterize the intolerant spirit of those Puritans in Massachusetts, it must also be mentioned that in 1692 various "witches" were found, forced to confess their sacrilege, and finally hanged. About fifty had to plead "guilty"; twenty were actually killed. One official, who had refused to arrest the accused at the very beginning of these atrocities, was himself seized and executed. The Rev. [George] Burroughs, who likewise rebuked the disgraceful proceedings, had to die, like the "witches," on the gallows. An old man who did not want to defend himself against the accusation of witchcraft, because he saw that every interrogation would end in condemnation anyway, was strangled in a barbaric way.

The real author and emphatic promoter of these atrocities was the old "king's servant" Rev. Cotton Mather. When the legislature assembled in October, 1692, many petitions were presented to it for protection against the witch trials. This Mather feared, and therefore wrote a book ("The Wonders of the Invisible World"), in which he sought to prove that not only did the heinous sin of witchcraft exist among the people, but that the proper means had hitherto been taken to eradicate it. The legislature, however, abolished the special court which had conducted these witch trials, and the people further did not permit "witches" to be tried in the ordinary courts. Many of those who had acted in this terrible history later confessed their wrong; but Mather defended his conduct to the death. —

Even before the Revolutionary War, the Episcopalians in Massachusetts had been released from the maintenance of Congregationalist churches. Since they were scattered throughout the colony, they were allowed to form "poll-parishes," i.e., congregations consisting of scattered individuals who were not bounded by any geographical line. Only they and the Congregationalist congregations were considered rightfully existing corporations, and as late as 1811, the Massachusetts courts ruled that no one could pay the church tax required of him by law to any church other than an incorporated congregation. It was not until 1823 that these laws were completely repealed, and since then written certification that one belonged to any church was sufficient to be exempt from the support of the parochial church. But whoever could not produce such a certificate was still considered later as belonging to the Congregationalist congregation and therefore had to pay his church dues.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments only accepted when directly related to the post.